New U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Museum Shows Alum’s Handiwork

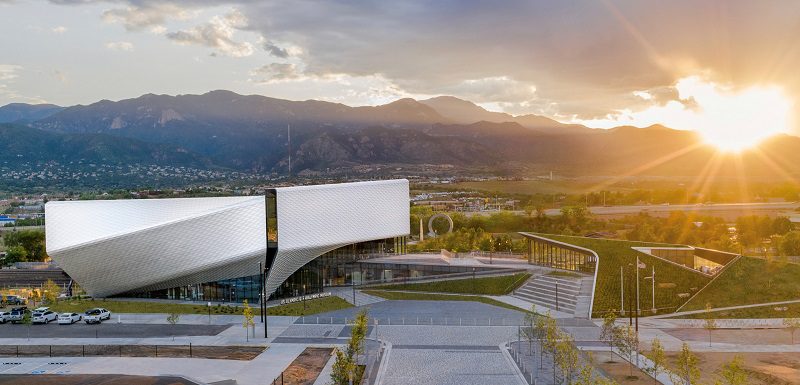

Last week’s opening of the United States Olympic and Paralympic Museum in Colorado Springs, Colorado, was especially sweet for alumnus Sean Gallagher (B.Arch. 2000). An associate principal and the director of sustainable design at the acclaimed New York City-based firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), Gallagher produced the original concept design that won DS+R the contract. The competition for the museum, which pitted DS+R against other high-profile firms Morphosis Architects and REX, took place in 2014.

“It was the first big pitch I did with DS+R,” he said by phone recently. “It was a big deal for me.”

Gallagher’s ambitious vision was shaped by two progressive ideas. First, since the museum is for both the Olympics and the Paralympics, accessibility was paramount.

“We wanted everyone to be able to experience the museum in the same way.”

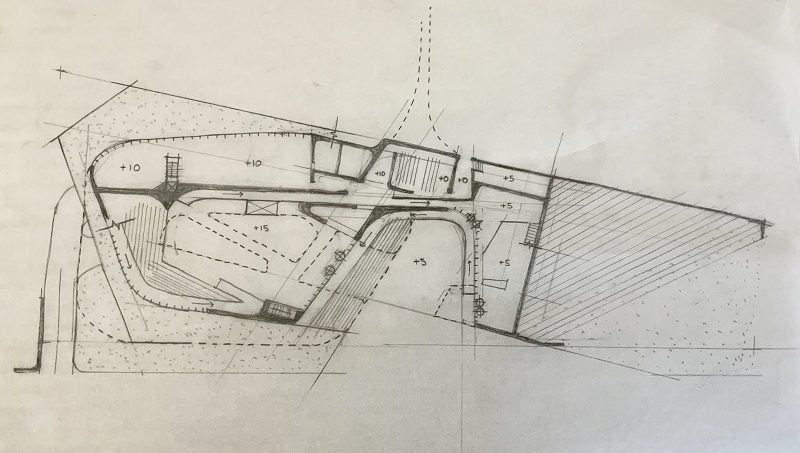

He and the team imagined the rotational technique used for the shot put competition – an athlete winding up for the throw – and decided on a spiral design with one long ramp and no stairs.

“Inspired by the energy and grace of the Team USA athletes and the organizations inclusive values, the building’s dynamic spiraling form allows visitors to descend the galleries in one continuous path,” reads the project description on the DS+R website. “This main organization structure enables the museum to rank amongst the most accessible museums in the world, ensuring visitors with and without disabilities can smoothly share the same common experience.”

“Inspired by the energy and grace of the Team USA athletes and the organizations inclusive values, the building’s dynamic spiraling form allows visitors to descend the galleries in one continuous path,” reads the project description on the DS+R website. “This main organization structure enables the museum to rank amongst the most accessible museums in the world, ensuring visitors with and without disabilities can smoothly share the same common experience.”

Gallagher’s second defining concept grew out of the site for the museum and his passion for “eco-systems thinking.” At the base of the Rocky Mountains, Colorado Springs is “all about the air and the elevation,” he said. And the museum was being built right next to a coal power plant that was being retrofitted with air-scrubbing technologies to help reduce the carbon emissions. What if the museum could help clean the air, the way trees do?

Gallagher was fascinated by the new breathable fabrics developed for athletes, which could be infused with titanium dioxide as a photocatalyst that would sequester carbon dioxide and convert it into energy. If such a “skin” enveloped the museum, it could capture the mountain breezes and function as an air filter.

Unfortunately, there just wasn’t time for the technology “to gain momentum,” he said. But “internal interests find other opportunities,” and Gallagher has two other projects that he hopes will realize that dream. In the meantime, the 60,000 square foot U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Museum does incorporate LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) initiatives, making it a “green” building.

Gallagher served as project director and project architect for the Olympic and Paralympic Museum from the competition phase through the schematic design phase. In 2015, he passed the torch to colleague Holly Chacon and moved on to other projects, most notably the Rubenstein Forum at the University of Chicago, which is set to open this fall and for which he has served as project director and principal in charge. Gallagher will also have those roles in the design of the new Discovery Place Science here in Charlotte.

Gallagher served as project director and project architect for the Olympic and Paralympic Museum from the competition phase through the schematic design phase. In 2015, he passed the torch to colleague Holly Chacon and moved on to other projects, most notably the Rubenstein Forum at the University of Chicago, which is set to open this fall and for which he has served as project director and principal in charge. Gallagher will also have those roles in the design of the new Discovery Place Science here in Charlotte.

Originally, he had planned to take his family to Colorado Springs for the museum’s opening, but COVID-19 kept them all home in Jersey City, N.J. He did, though, show his two daughters, ages 7 and almost 9, photographs of his original drawings along with a video of the finished project.

“They said, ‘That’s your project? You did that?’ They think it’s really cool.”